Who thought saying “No” in Japan would be so hard?

A little bit about “reading the air” in Japan and why saying no is hard

The other day my friend asked me, “How do I tell if a Japanese person is saying maybe or no?” It should be straight forward, right? Well, not exactly. In Japanese culture, it is highly impolite to directly say “No.” As a result, many Japanese people will find softer, indirect ways to decline that may not be the most obvious. Sometimes I even have trouble understanding what Japanese people say versus what they mean.

We will explore “what reading the air is”, how Japanese people say no, and how you can read the air and understand one of the quirks in the way Japanese people communicate.

What does it really mean to “read the air”?

“Reading the air“ is all a part of a greater type of communication in Japan called “Ba no Kuuki wo Yomu” (場の空気を読む), literally, “reading the air” or “understanding the situation without words.”

Let’s break down the Kanji:

場の空気を読む: Ba no Kuuki wo Yomu

場: Place; scene

空気: Air

読む: To Read

According to Daijisen, a Japanese dictionary, to read the air means “To infer the situation from the atmosphere. In particular what you should or should not do, what you want or do not want the other person to do, and what they want or don't want to do.”

To better understand why it can be so difficult to discern the true meaning of what a Japanese person is saying, it is probably more worthwhile to look into the broader cultural reason Japanese tend to communicate more ambiguously.

Why is reading the air an important part of communication in Japan?

To understand why Japanese people tend to be more contextual and indirect, it helps to understand some characteristics of Japanese culture. First, is the importance of harmony or wa (和). Wikipedia has a good definition: “[wa] implies a peaceful unity and conformity within a social group in which members prefer the continuation of a harmonious community over their personal interests.”

Because of the deep roots and strong importance of harmony, there are numerous ways it influences the culture, such as the characteristic of collectivism: putting harmony of group above the expression of individual opinions (Hofestede).

Collectivism can be further expanded on through the concepts of tatemae (建前 what is said) and honne (本音 what is meant).

Here is the kanji: 本: True; real; origin

建: To build, construct

前: Front

音: Sound; noise

Tatemae is how individuals and groups express themselves, it is the facade they chose to show, the words they chose to say. Honne is the actual true feelings and thoughts of the individuals. In simple terms, what is said vs what is meant. In lower context cultures, these two things typically align, what is said is what is meant. However, in high context cultures like Japan, what is said, is often not what is meant or truly felt.

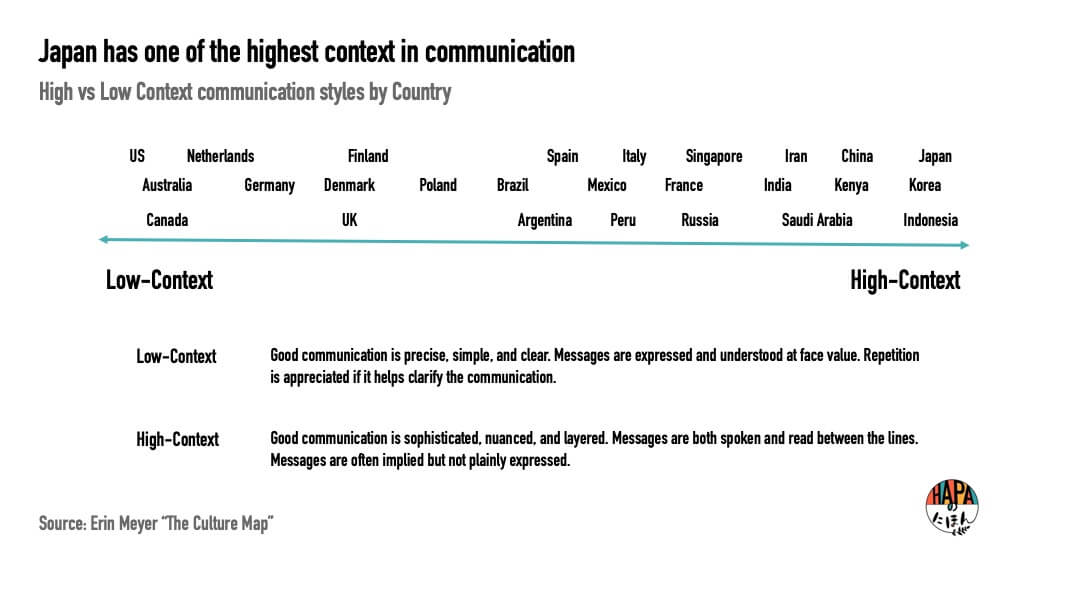

Now, you may be thinking, “but every culture has some degree of collectivism, harmony, and tatemae and honne.” This is true, but the important distinction here with Japan and other cultures is the relative importance of these attributes to other types of characteristics. Take the context style of communication for example – below is a figure from Erin Meyer’s book “The Culture Map” showing the relative context levels of communication in several different countries’ cultures.

You can see that context level varies on a sliding spectrum and a culture’s communication style cannot simply be put in one or the other. What is interesting about this concept in Japanese culture, is that it is mostly about groups and the groups’ actions, not individuals’. From a group lense, tatemae is what the group thinks, does, and is accepted in the group; whereas honne is how the individuals in the group actually feel.

For example, in a business setting, a marketing team may be required to run a certain marketing campaign, and while not everyone on the team is favorable in doing it, no one says anything (shows honne) because it is something that is required by their boss. Japan’s ability to value tatemae is one of the keys to creating harmony and conformity in society.

Is being able to read the air that important?

People in Japan who can’t read the air, are known as “KY.” This stands for K - kuki ga (空気が air) Y - yomenai (読めない can't read). Literally “cannot read the air.” As you may expect, this is considered an insult. This word “KY” came to be in 2007 and grew so popular that it was nominated to the New Word Buzzword Prize. Now it is common slang.

Aside from the possibility of being ridiculed for being a KY, there is evidence that over the past couple decades, reading the air has become more vital in Japanese culture.

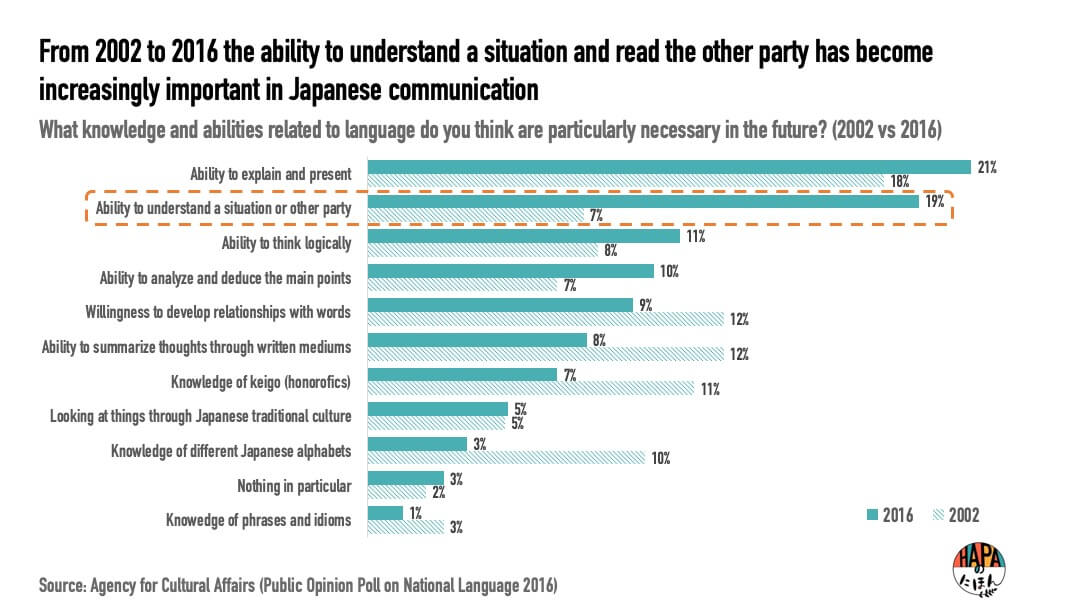

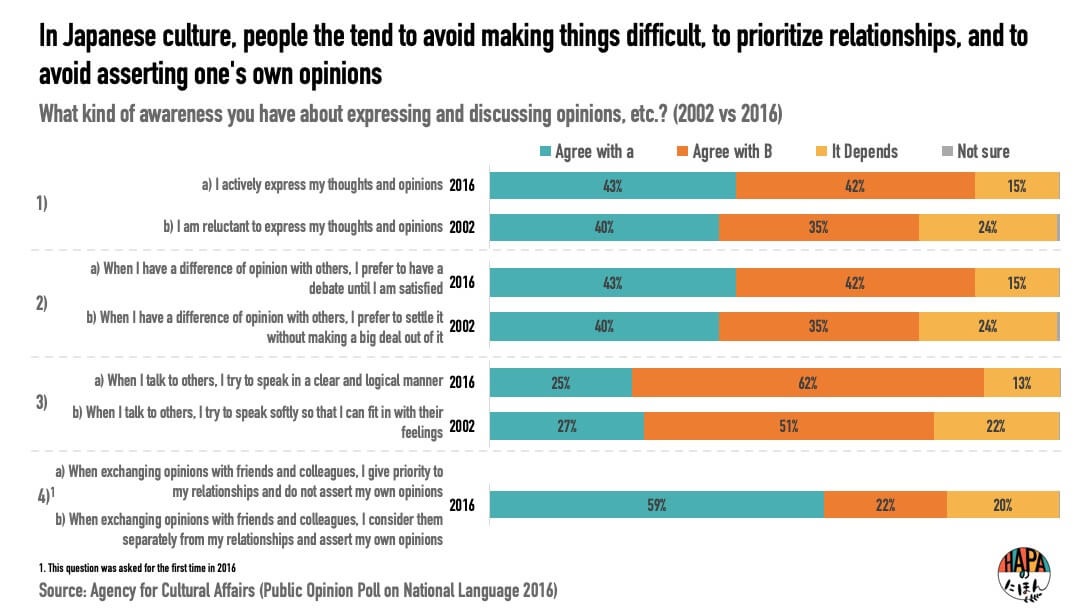

Every year, the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan conducts a study called the “Public Opinion Poll on National Language.” Like the name suggests, it is a survey on the public’s opinion on the Japanese language and covers topics ranging from people’s understanding of kanji, honorifics (keigo), the current state of language, and the current state of language communication, such as conversations and letters. The purpose is to create a reference to inform Japanese language policy. Respondents are citizens from all over the country who are over 16 years of age.

In the 2016 study the survey asked participants, “What knowledge and abilities related to language do you think are particularly necessary in the future?” The most important skill was “the ability to explain and present.” The second most important item is the ability “to understand people and situations,” in other words, the ability to read the room. What else is interesting about this, is that it was the knowledge/ability that changed the most in 14 years, jumping from just 7% to 19%.

(Unfortunately this question was not asked in more recent surveys. It would be great to see how this metric is tracking now.)

The fact that the ability to read a room is almost as important is the ability to explain or present is quite astonishing. Furthermore, in a question that asked respondants about their attitudes toward expressing opinions and discussions, 62% of the respondents answered that when they have a difference of opinion with others, they "prefer to settle the matter without causing trouble," an increase of 10% from 2008, when a similar question was asked.

In previous surveys, respondents have been asked about their “Awareness of expressing and discussing opinions” through 4 different questions (graph below.) It found Japanese people have a tendency to avoid making situations difficult, speak in a way that is considerate of others, and prioritize relationships by not asserting one's own opinion.

“Adapting to another person” and “Ability to understand people and the situation” are synonymous with reading the air. Japanese people are heavily conflict avoidant and will try to mitigate direct confrontations. If someone asks if you want to hang out, and you don’t really want to, responding with “I am busy” is much less harsh than a direct no. Therefore it’s common to use ambiguous language. If you are unable to read between the lines, then you missed the message.

Itsukushima shrine

Thoughts about reading the air in current society

Do Japanese people really read the air? Are Japanese people tired of reading the air?

Manabu Nishigawa, an associate professor at Kansai Gaidai University, states “that in recent years, the inability to read the air is seen as a bad thing.” He continues to write that in Japanese inward facing groups, those with minority opinions are pressured to confirm to think and act as the majority around them. Consequently, people speculate rather than read the air, since they must think and act the same way. In other words, instead of actually tuning into the true meaning of the situation, people are reading the situation as they have concocted in their head.

The author suggests that people just assume instead of truly listening (and reading the air) carefully to understand what the person wants or feels. In other words, Japanese people think ahead of what the other person wants or desires, and act based on their own judgment of the other person's feelings. Given the amount of social energy required, Nishigawa suggests Japanese people are tired of reading the air.

Reading the Air in the media

“Reading the air” is a common theme in Japanese media as there are many books, TV show topics, and articles.

For example, in 2020, a show called “What is the difference?” on TBS (Tokyo Broadcasting Station) released an episode on how to tell the difference between those who can and can’t read the air. They showed in particular, 4 traits of those who can

not read the air.

1. Inability to understand timing: For example, when a coworker is trying to leave the office, you ask them for help

2. Inability to understand social distance: For example, you join someone’s trip when you don’t know them well

3. Lack of understanding of the flow of situations: For example, you start to do your makeup and hair and make everyone wait for you before taking a group photo

4. Lack of understanding of the others feelings: For instance, you keep singing breakup songs at karaoke because you’re sad, regardless of what others around you want to sing

There are other TV shows where this topic has surfaced as well. One of which is called “Chico Chan will scold you” (チコちゃんに叱れる) – a show about a 5-year old character who asks a Japanese comedian questions. The question on the January 2021 show was “What do you do to read the air?” The answer according to Chico-chan is, “Looking at someone’s true intention for 0.2 seconds.”

What Chico-chan means is reading someone’s facial expression to understand their true intention.

Through these two TV show episodes, you can see the differences in interpretation of what it means to read the air and how prevalent they are in Japanese society.

Similarly, if you search on a search engine, there are countless business articles about the importance of and how to read the air, suggesting that if one cannot read the air, then one can’t do the job.

Kagoshima

How do you say no in Japan? (And other tips)

To say no in Japan, there are a couple distinct body language and verbal cues one can use, such as delaying their answer, tilting their head, pretending to think, and saying “maybe.”

There isn’t a basic formula to read the air and it simply takes practice and awareness. Similarly, to other languages and cultures, I am sure the following tips apply as well.

Three important aspects:

- Language (words, tone, response time, intonation)

- Body language

- Social dynamics (the relationship between the individuals)

Overall, general awareness of others behaviors and language in tandem of how an individual conducts themselves and how this influences others is key. It is definitely much more socially exhausting, but will help you better communicate with Japanese people.

Final Thoughts

I hope this provides some insight into why Japanese people communicate the way they do and how you can better communicate with them (and other high-context cultures!) Even I struggle at times to read the air and at the end of day, it just comes with practice and being cognizant of the situation and the relationships of those around you.

It should be noted that the ability to read the air is not unique to Japanese culture. Rather, it is a more important aspect of the language and culture relative to others. In English, there is a phrase to “read between the lines” or “read the atmosphere.” In Italian it's the same phrase to read between the lines, “leggere tra le righe,” as well as German “zwischen den Zeilen lesen,” (With this, it is also likely that similar languages such as Spanish, French, and Dutch have similar phrases). In Finnish one could “haistella ilmaa” which means to sniff the air. And in Dutch “er hangt iets in de lucht,” which means “there is something in the air”, not quite a direct translation, but similar in that it implies there is something ominous or distinct about the situation.

(Please note, I am not a language expert: please let me know if something is incorrect. Or if you have a saying in your culture you would like to share!)