How Japan does city planning by not doing city planning?

A look at how Japan’s zoning laws and geography have contributed to what Japan’s urban landscape is today

Walking down a block in Tokyo, one can come across a temple, a doctor’s office, an apartment complex, and even small commercial businesses all within 100 meters. Many roads are so narrow and winding that pedestrians, bicycles, and cars share the same space.

Why does Japan – and especially Tokyo – look like this? I’ll highlight three key characteristics that have contributed to what Japan looks like today.

Characteristic 1: Land-use laws are governed by national law

Land-use in Japan is governed by national laws rather than regional or local ordinances. Nonetheless, local municipalities have power through application, with respect to the law.

As a result of the national zoning system, regional and local governments have less power, which means that the laws are less likely to become capricious and biased towards certain socioeconomic classes. On the flipside, if a local area experiences land use problems, it becomes difficult to manage these at a local level.

Wow, that was a lot. Let’s back up a moment and break down the previous paragraph. To put “laws are less likely to become capricious and bias towards certain socioeconomic classes” into context, the US, for example, has given the power of land-use regulation to municipal governments. In New York State alone, the over 1,600 villages, towns, and cities are each able to adopt their own land-use laws. One of the many consequences of this is that zoning laws were created in line with racist and classist intentions and effects, such as housing affordability problems and segregated neighborhoods.

The end of a shopping street with wide widewalks

This is often caused by homeowners’ desire to preserve the value of their property and neighborhood. There is a term coined: “Not in my backyard” or “NIMBY”.

NIMBY is used to describe communities that act in their own interests and oppose nearby developments that they would otherwise support and benefit from if the developments did not take place near their area. - Corporate Finance Institute

To help you understand the basic concept of NIMBY, here is a simple example of Neighborhood X. A new apartment complex is proposed to be built in the neighborhood as the town severely lacks housing. Residents of Neighborhood X are worried that this new apartment will create an obstructed view and bring more noise and traffic. For these reasons they oppose it and fight back and as a result the apartment is either built someplace else or not at all. Other common examples are airports, waste facilities, and affordable housing projects.

NIMBYism is a big problem in the US, and Japan still faces NIMBY issues as well (recently, there has been strong opposition to children’s daycares due to noise complaints.) That said, as stated above, Japan is less likely for laws to end up as fractured as the US. In Japan, if your next door neighbor decides to tear down their house and create a duplex and starts renting them out, you can’t do much about it.

Characteristic 2: Japan essentially only has mixed-use zoning

So now we understand that Japan’s land use laws are governed by the national government, but what exactly does this look like?

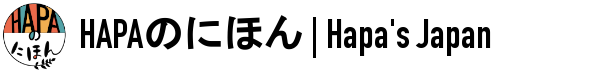

Japan has only 12 types of zones (see the figure below), and they are all essentially mixed-used. For those who are not familiar, just like the name “mixed use”, it means that the area can be used for multiple things. Hence, there are hardly any areas in Japan with just one type of building. Almost every major area in Tokyo, for instance, is diverse, being filled with single-family homes, multi-family homes, small business, industrial business, and religious institutions just to name a few. Strong emphasis is on single-family and multi-family homes—there is no distinction between the two. (I will go into this further in the article.)

To give some perspective for those who have not been to Japan, in my block of ~4,800 square meters (~51,667 square feet), there is a shrine, dentist office, bakery, metal workshop (creates iron products) but mostly apartments and some houses.

Since the government has allowed such inclusive zoning laws, it has allowed the market supply to respond to demand changes. In other words, if there is a sudden surge in the need for housing, schools, or businesses, there is a lot of flexibility.

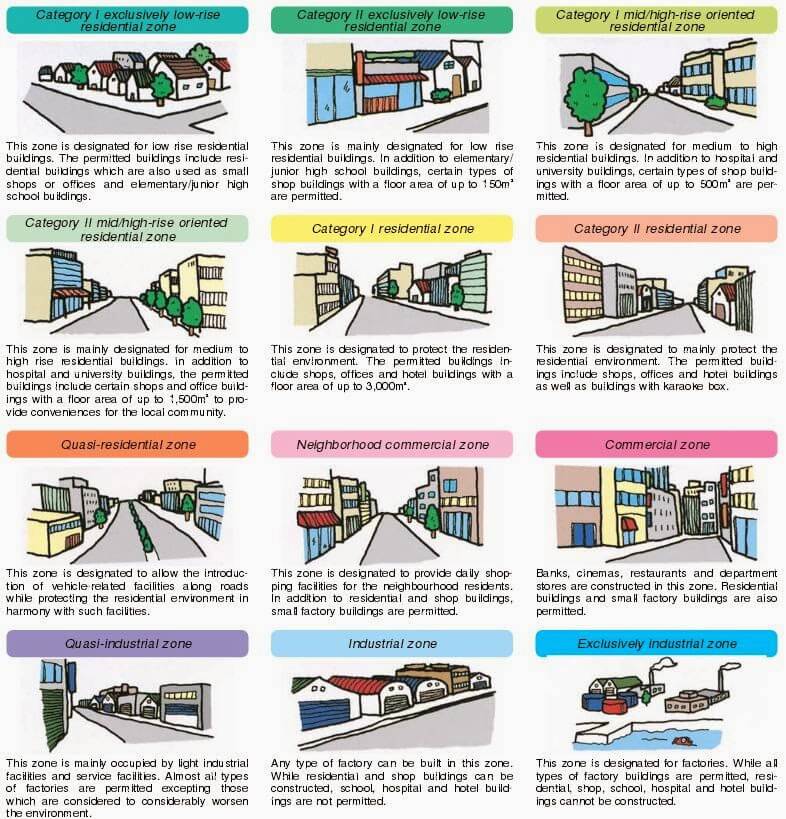

For instance, Tokyo has consistently had more housing stock (dwellings) than households for the last 30 years.

While the number of vacancy dwellings in Tokyo is increasing, the vacancy rate over the last 30 years has hovered around 11%. Tokyo has kept pace with its increasing population by adding more supply, keeping an abundant amount.

Major cities like London, San Francisco, and New York City are known for housing shortages and sky rocketing rents. Have you heard about housing shortages in Tokyo?

Characteristic 3: Winding Narrow Roads

Japan is known for its winding narrow roads. This is not due to one reason, but thought to be caused by a variety of factors.

The first hypothesis is that Japan never really had a horse-drawn carriage culture, and streets were predominately used by pedestrians, meaning that there was not necessarily a need for wide roads. It is thought that since Japan lacked this time in history, roads remained narrow.

There are also a lot of one-way roads due to the hills as well

A second contributing factor is from the Meiji Restoration (during the Meiji era 1868-1912) when Japan underwent major modernization and westernization. In this time period, Japan’s government chose to focus on building up railroad infrastructure rather than roads for an automobile-centric transportation system.

Another factor is that Japan is simply a mountainous country – with approximately over 80% of the landmass occupied by mountains. Due to the topography, there isn’t that much space to build on. By having narrow streets, the area for traffic is minimized leaving it to be used as a building area instead.

For now, I have listed three factors. There simply isn’t just one reason or simple answer to why Japan has narrow roads but my research validates the reasons discussed above.

What does this all equate to?

Interesting Cities

"...frequent streets and short blocks are valuable because of the fabric of intricate cross-use that they permit among the users of a city neighbouhood." ― Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Jane Jacobs contends that the more people walk down a street, the more colorful it becomes. The more people walking on a street, the more interesting the street becomes. Short streets force pedestrians to take alternating routes, which gives businesses who aren’t on that main road a chance.

Rainy Night in Tokyo

Japan’s zoning laws and narrow roads are the perfect formula for this. You could be walking past a series of housing and suddenly find a hole in the wall 5-star restaurant. People can stay in their neighborhood to do errands. Within my neighborhood, I can walk to the doctor’s office, grocery store, shoe repair, book store, appliance store, you name it. Of course, there isn’t everything, but I believe this has allowed Japan’s neighborhoods to develop strong communities. There isn’t a day I don’t see two Grandmas or Grandpas talking on the side of the road as they pass by, or see the baker talking with kids on the way back from school. It’s truly heartwarming.

Furthermore, Japan is very hilly. The hills and rivers throughout Japan add character and adds a nice aesthetic to neighborhoods. Houses built on hills often have interesting architecture as well.

Affordable housing

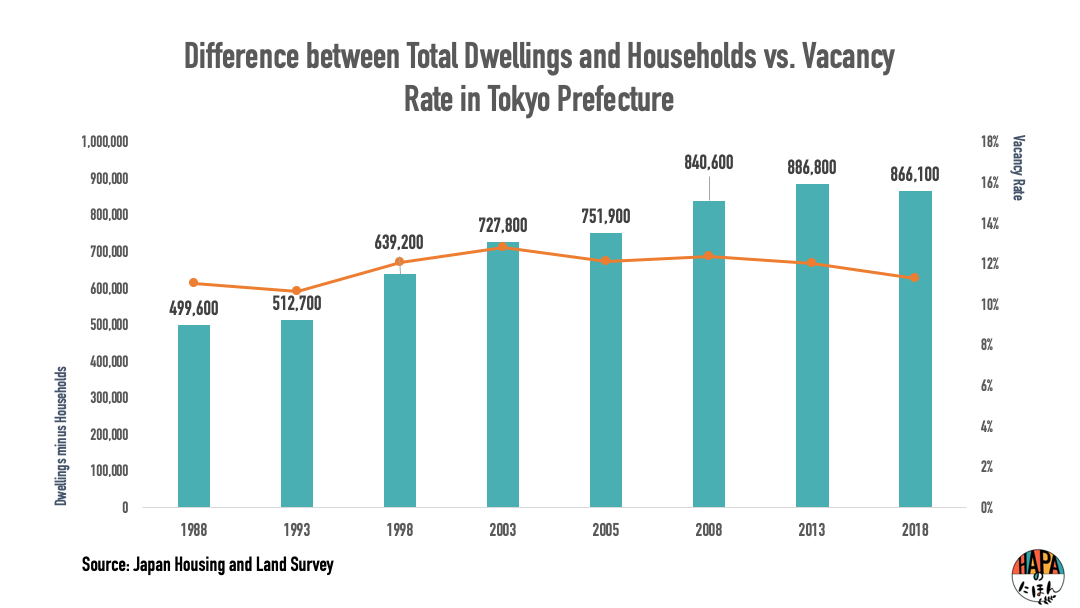

11 out of 12 zones allow for residential development, and as mentioned above this is not differentiated between single and multi-family homes. The only zone that doesn’t have residential housing is the “Exclusively Industrial Zone” where there can be factories with “strong possibility of danger or environmental degradation.” No one should be living in such an area anyway. This in turn has provided Japan with affordable housing, as people can live almost anywhere, as housing generation is not hindered. To provide some context, The Financial Times published the below graph in 2016.

Despite an increase in population, Tokyo’s housing prices did not exceed the growth of population. Minato-ku is in this graph for a special reason. It is one of the centrally located wards of Tokyo, and home to Tokyo Tower, lavish neighborhoods, and of course, the highest rents. Even Minato-ku with its prime real estate still does not see housing prices outpace population growth. Now that says something.

Some Problems

Naturally there are problems with the zoning laws. Some areas are ugly, there is constant construction, and some neighborhoods are dirtier due to some industrial and commercial businesses. In addition, there have been problems conserving historical sites. Narrow roads are dangerous when are there natural disasters such as earthquakes or fires, and driving can be difficult and cause accidents.

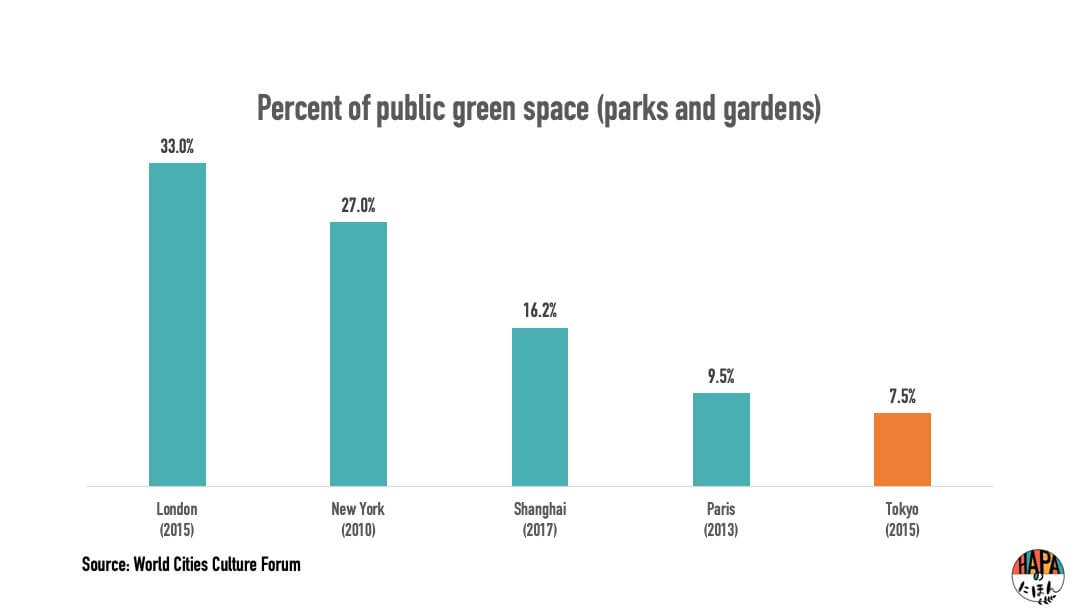

Furthermore, there is a lack of green space in Tokyo.

While yes, there are many parks, these parks are often just playgrounds on gravel. Tokyo does have beautiful parks and greenery, but it tends to be concentrated, rather than spread around the city. But this issue expands far beyond zoning laws and narrow streets.

A standard park in Tokyo. Not too much green.

Obviously, this is not a perfect system, but there are some things that can be learned from Japan.

Final thoughts

Japan is a beautiful place, where a walk in the neighborhood is often filled with discoveries. The different combinations of routes from point A to B are countless. The zoning system is not perfect, and narrow streets are annoying and have problems of their own, but they have contributed to creating what Japan looks like today. Next time you’re in a Japanese neighborhood, I encourage you to go down that side road, take a different route, and simply enjoy wandering.

Citation:

Fielding, A. J. (2004). Class and Space: Social Segregation in Japanese Cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(1), 64–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3804429

Land Use Law Center Pace University School of Law (n.d.). (publication). BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO LAND USE LAW (pp. 4–4).